The Silk Road to Mustang

Nepal was in a holiday mood. The monsoon clouds were finally gone, tossed into the jetstream by the strong west wind that now floated paper kites above the rooftops of the small, low villages along the broken highway. Dust everywhere, like oxygen. The marigolds waved in full bloom alongside sleeping heavy equipment, nestled under thick blankets of dust. This week, fixing the road would have to wait.

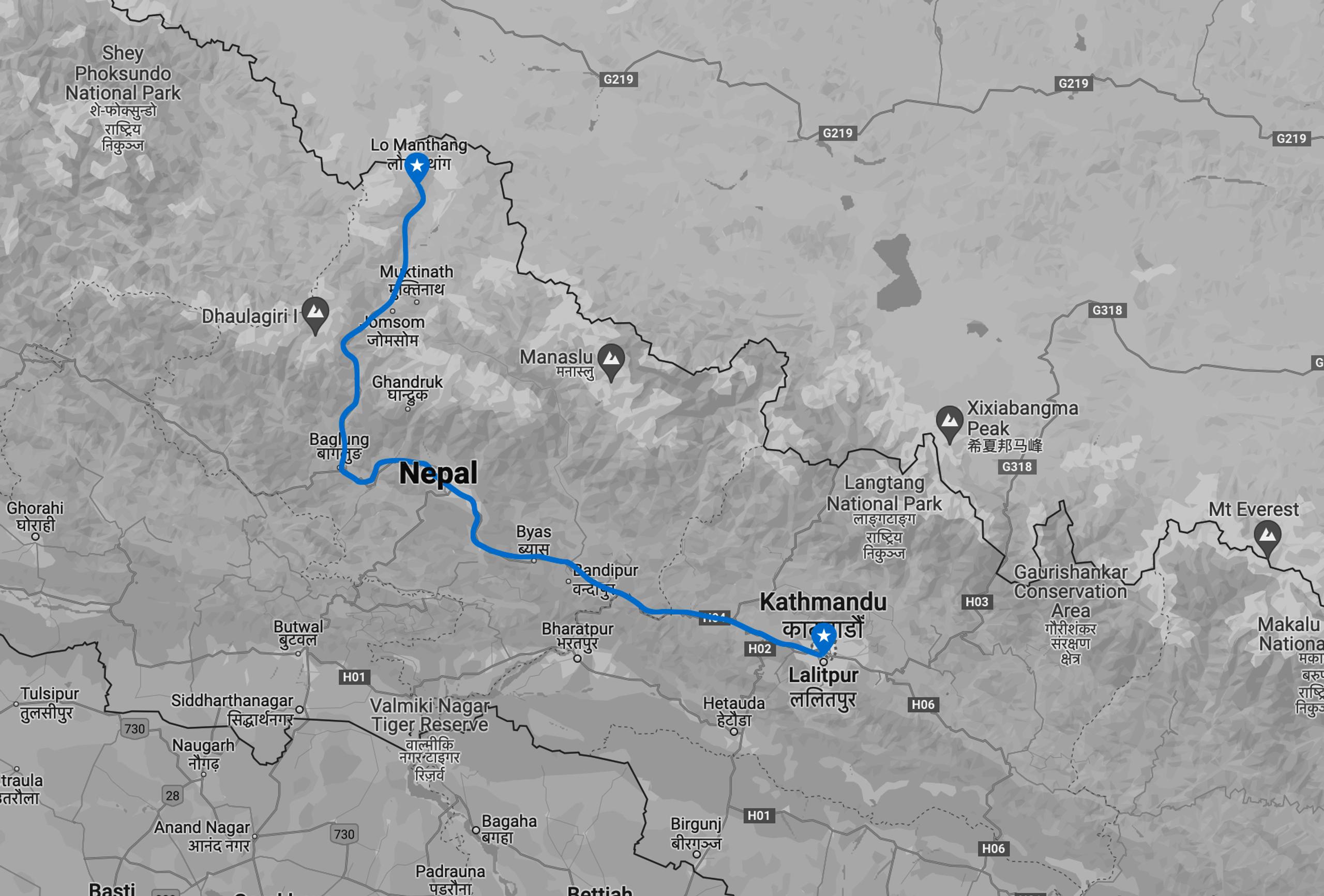

It’s only 300 miles from Kathmandu to Lo-Manthang — a healthy American half-day, or maybe a full day on a slow road, or if you were thirsty for beer. But here in Nepal, this is four days minimum — more if the altitude hits hard, if the old bikes break down, or if a bus gets stuck on the narrow ribbon of dirt and sand between the cliffside and the void. Most days, we knew, would involve all three.

Cory learned how to ride motorcycles by watching a YouTube video a week before he left the States. As we left Kathmandu, he was as wobbly as a young horse, too scared even to stop and take photos. Soon enough, though, he found the throttle. While it wasn’t exactly smart to go faster on these roads, it was certainly easier - luck favors entropy, after all.

Todd rode in the same way he lives: coiled as tight as a hammer spring, heavy on the throttle, rattling and buzzing and passing on the wrong side. We’re all far too old for this shit, and Todd especially so. Still, he rode like an eighteen-year old — all bluster and roulette, an admirable disregard for whatever lay around the next blind curve. By the grace of god, his bike slowly disintegrated on the impossibly rough road and his pace slowed to something more aligned with survival.

Our highway split and narrowed as it clattered out of the jungle. The Himalayas, first whispering and aloof, grew closer and choked the horizon. Fractured granite walls crowned with seracs towered over the road with icy peaks scratching the stratosphere. Simultaneously seductive and terrifying, we couldn’t pull our eyes away from them. And these weren’t the kind of roads you really wanted to look away from.

Still days to go, we stopped leaning into the corners and instead stood upright on the pegs, rodeo-riding over boulders and deep sand, through wild rivers under which the road temporarily disappeared. We inched along a cliffside single track as the Kali Gandaki river gorge, the deepest in the world, cinched around us, robbing our sunlight. Rice fields and banana trees gave way to pine forests and the smell of snow. The atmosphere dried as we gained altitude: still pounding towards nirvana.

After three long days, we were alongside the mountains and then, in an instant, beyond them. The terrain flattened and we picked up speed, skittering across the loose gravel. The landscape widened and rose into steep cliffs buckshot with ancient caves. Prayer flags shivered in strings above square villages exhaling woodsmoke, fortified against long-forgotten enemies. The river widened into braids like a horse’s mane. Mustang.

The bikes breathed hard and fouled plugs in the thin air. Batteries groaned and gave up in the cold. We sought solace as travelers here have always: under the graceful gaze of gods painted some six hundred years ago, in old friends, in moonshine.

On the fifth day, we sputtered into Lo-Manthang, down to only two bikes. On the ridge above the 14th century oasis city, we paused and stared across to the last spine of mountains below Tibet. A forgotten place, this. At least to us. Off of the bikes at last, we followed the low beams of sunshine across the city’s steep canyon streets, talking with the locals, sharing tea. Without exception, they loved Cory’s tattoos. They asked me how far I live from Queens, New York — where most of their family now lives. We exchanged numbers and promised to call.

And that, after all, is why we came: to laugh with strangers, and at ourselves under the influence of the snowy peaks, history and dust. Intoxicated by this long game of suffering screaming and gasping, all-knowing that once we arrived, all that remained was turning around and rattling back home again. Everywhere that might be.

Text by Ben Ayers

Photos by Cory Richards